And they're off! The nominations for the 78th Annual Academy Awards, announced on Tuesday, are a reflection of a movie year pervaded by topical, edgy and independent features. Only one of the Best Picture nominees – Steven Spielberg’s Munich – could be considered a major studio release, capping off a dreadful year for Hollywood movies. This year also brought a fresh injection of nominees into the Academy where 16 out of the 25 acting and directing contenders are first time nominees. This is a trend that has been ongoing for a number of years and has served to lower the average age of the Academy considerably and make the organisation more inclusive of smaller, indie films.

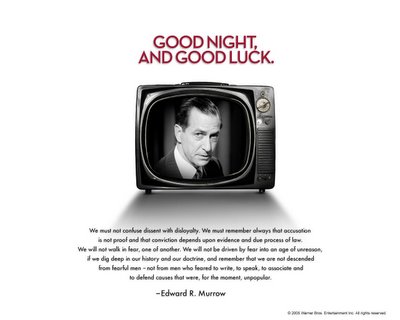

As expected, Ang Lee’s heavily lauded gay love story Brokeback Mountain leads the field with 8 nominations. It heads the Best Picture list along with melting pot drama Crash and George Clooney’s McCarthy-era journalist pic Good Night and Good Luck, both of which scored 6 nods. Spielberg turned the tide on a mountain of negative (and unjustified) criticism to land Munich nods for Picture and Spielberg himself as Best Director. The last place on the roster went to Capote, Bennett Miller’s biopic of writer Truman Capote.

Lee received his second Oscar nomination as Best Director for Brokeback whilst Steven Spielberg landed his sixth nomination for Director, having won this award twice for Schindler’s List (1993) and Saving Private Ryan (1998). George Clooney (a triple nominee), Bennett Miller and Paul Haggis (Crash) complete the list with their first nominations for Best Director.

Golden Globe and SAG winner Philip Seymour Hoffman heads the Best Actor race, with his first nomination for playing flamboyant ‘In Cold Blood’ author Truman Capote in Capote. He’s joined by another adored character actor, David Straithairn, who plays journalist Edward R. Murrow in Good Night and Good Luck. Joaquin Phoenix got his second Oscar nomination for his Golden Globe winning role as Johnny Cash in Walk the Line. Australian actor Heath Ledger (Brokeback Mountain) and Terence Howard, as a pimp-cum-rap star in Hustle and Flow, are first time nominees.

Hoffman is the early favourite, having won every pre-Oscar award going but a late show of support for Ledger could intensify the race. I think the one to watch for here is Straithairn, who was singled out for praise by Hoffman as he accepted the Screen Actors Guild award last Sunday night. Like Hoffman, he is a revered character actor who has worked with just about everyone in Hollywood and I think the end race will be between these two semi-veterans.

Reese Witherspoon landed her first nomination for Best Actress for her role as chirpy singer June Carter in Walk the Line. She’s joined by two former winners, Charlize Theron (Best Actress, Monster, 2003) who plays a sexually harassed miner in the poorly received North Country. The magisterial Dame Judi Dench, who won an Oscar for an 8 minute cameo in Shakespeare in Love (1998), got her fifth nomination for playing sprightly widow Laura Henderson in the so-so Mrs Henderson Presents. The list is completed by Felicity Huffman for her gender-bending role in TransAmerica and, in the biggest surprise of the day, 20 year old Keira Knightley for her Elizabeth Bennett in Pride and Prejudice.

Knightley no doubt benefited from a high profile snub from her own British Academy who failed to nominate her for a Bafta. Witherspoon and Huffman won the Golden Globes but Witherspoon gained an early advantage by claiming the SAG last weekend. It’s still all to play for but this really is a two-woman race with these very different actresses, playing very different characters, going neck and neck.

George Clooney received one of his three Oscar nominations (Director and Screenplay in addition to here) for his role in Steven Gaghan’s explosive Middle East oil thriller Syriana. Paul Giamatti, snubbed last year for his role in Sideways, gets his first nod for Cinderella Man. Jake Gyllenhall makes his Oscar debut for a lead role in Brokeback Mountain as does Matt Dillon for his revelatory turn as a racist cop in Crash. The last place was a surprise also: William Hurt for his cartoonish cameo as a psychotic mobster in David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence.

This is an exceptionally strong category that could really go any way. Giamatti won the SAG last weekend and will have a well of sympathy votes this year from balloters seeking to correct such a grave wrong from last year. I’d personally like to see Matt Dillon win for his brilliant performance and he may well become the receptacle for the Crash votes as the movie is unlikely to win in its other categories. The safe money is on George Clooney, who has had a remarkable year as an all-round Jack of All Trades. He’s the Hollywood choice and might well become the first person to ever win an acting and writing Oscar on the one night.

British Actress Rachel Weisz continues her march to the podium by landing her first nomination as Best Supporting Actress for the criminally under-represented The Constant Gardener. She leads a strong field of indie actresses, amongst them former winner Frances McDormand for playing a Lou Gehrig’s stricken miner in North Country. Catherine Keener, nominated in this category six years ago for Being John Malkovich, is nominated for her turn as ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ author Harper Lee in Capote. Michelle Williams, a former star of teen angst drama Dawson’s Creek, receives her first nomination as Heath Ledger’s slighted wife in Brokeback Mountain. The last place goes to Amy Adams for an acclaimed turn in hit indie feature Junebug.

Adams is really one to watch out for here. She has fought tooth and nail for every vote to get to this point. There is genuine support in Hollywood for this former unknown, who has built up a steady CV with turns in The West Wing, Buffy, Smallville and the American The Office. Enough voters have seen her movie to nominate it – or are at least aware of it – so she is the underdog dark horse in the race. Weisz will be hard to beat, having won the Golden Globe and the SAG but the movie’s failure to land any more major nominations hurts her chances. I’m rooting for Williams who gracefully made her mark in Brokeback by way of a sympathetic and highly expressive performance.

The Original screenplay race is between Clooney’s Good Night and Good Luck, Crash, Syriana, Woody Allen’s Match Point and Noah Baumbach’s divorce comedy The Squid and the Whale. Clooney would be a good choice here although Paul Haggis, nominated last year for Million Dollar Baby, will also be a strong contender for Crash. I’d watch out for Baumbach, the outside favourite for a highly acclaimed movie that has been snubbed in the other categories.

Brokeback Mountain is an almost certain bet for the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay. It’s up against the screenplays for Capote (written by another actor Dan Futterman, best known for playing Robin Williams’ son in The Birdcage and for the TV shows Judging Amy and Sex and the City), The Constant Gardener and A History of Violence. The last writing slot goes to Munich, an outside shot with an impeccable pedigree. It’s written by Eric Roth, who won a writing Oscar for Forrest Gump (1994) and Tony Kushner who received the Pulitzer Prize for his play Angels in America.

Normally nominations day becomes bogged down in debate over who and what wasn’t recognised but this year there are few serious omissions. Walk the Line missing out on a Best Picture nod is about the size of it although it is fascinating to see the swing in favour of Spielberg and Munich.

The real fun starts tomorrow when the voting ballots are sent to the 5,000-strong Academy and the annual ‘eeny-meeny-miney-mo’ box checking begins. This year’s race has the potential to be predictable on an unprecedented level, what with there being so many early favourites. It will be interesting to see if major players, such as Brokeback and Philip Seymour Hoffman, can sustain their early momentum until March 5th, when The Daily Show’s Jon Stewart compeers the show for the first time. Watch this space.